They both emigrated to Paris, where they could show their work to a larger audience. There are Russian avant-garde artists whose works are also present in Western museums Natasha Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov come to mind. The first reason-the availability of his works and writings-is, in itself, trivial. Second, Malevich’s Suprematism gained rapidly growing appreciation with the rise of Western post-war abstraction, which it seemed to historically legitimise. First, his works can be found in Western museums and his writings are publicly accessible (at least in the German-speaking world). Neither Vladimir Tatlin nor Aleksandr Rodchenko-nor even El Lissitzky, who had the closest personal ties with the West in the 1920s-have enjoyed an appreciation comparable with that of Malevich. In the West, Malevich has become the paradigmatic figure of the Russian avant-garde.

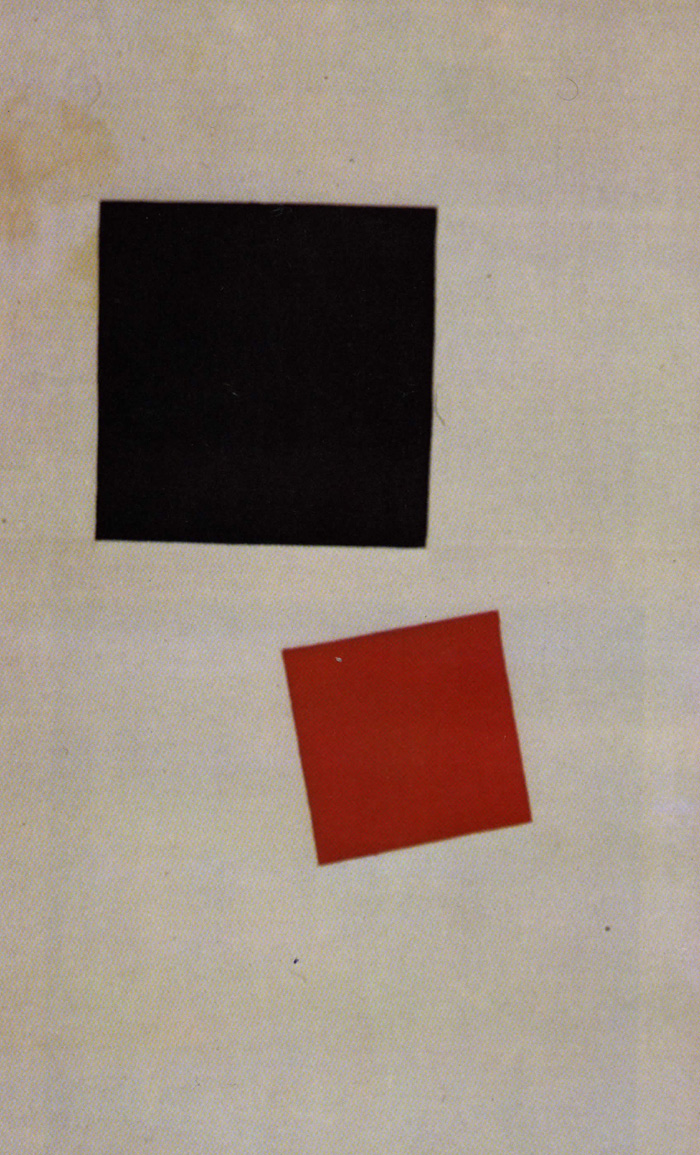

He had created something new and was well aware of its creative potency. Malevich did not “abstract” anything, because that would have meant starting with an object, a process he rejected. At the time, Malevich used simple titles such as Suprematist Composition, sometimes supplemented by the word “non-objective”, because he never used the term “abstract” in his life. Malevich showed his Suprematist achievements, 39 in number, for the first time in “0.10: the Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd in December 1915, and announced: “Things have disappeared like smoke to gain the new artistic culture.” Squares, triangles and, above all, beams in unmodulated colours (mainly black and red) spread across a white surface.

#Malevich metaimage full#

In the work of Malevich, however, these have enormous importance: he developed his ideas on notepaper before translating them onto canvas.īorn in Kiev, this Ukrainian artist of Polish descent is commonly associated with the Black Square, 1915, the somewhat irregular black shape on a white background that signalled both the end and beginning of all painting: the end of representational art and the beginning of Suprematism, the painting of the “highest order”, as he, in full missionary modesty, called the movement he founded. At first glance, it seems to be vast, with more than 500 pieces on show, but many are small works on paper. At the end of last year, the Stedelijk staged another Malevich retrospective, this time entirely in-house, which is due to arrive at Tate Modern next month. The show attracted visitors from all over Europe, eager to see the unfamiliar works-many of which, particularly his early paintings, had never even been reproduced.Īt the time, there was uncertainty around the dating of some of his pictures, and only gradually did it transpire that Malevich (1878-1935) had purposefully concocted an artistic biography in which he backdated some of his later works and included recreations. When the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam staged the first solo exhibition of the work of Kazimir Malevich in 1989, with loans from leading museums in the Soviet Union, it was a sensation. The Russian-Soviet avant-garde of the 1910s and 1920s is now well known in the West exhibitions in Frankfurt, Düsseldorf, Munich, Berlin and Cologne have familiarised us with all aspects of the movement and its artists.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)